By: Vanessa D. Miller*

Published: 3/19/18

The United States Census Bureau (“the Census Bureau”) is preparing for its twenty-fourth national census. Since 1790, the United States Census (“the Census”) has provided the government with crucial demographic information about the nation’s population. It collects data on the age, race, ethnicity, sex, familial relationships, educational attainment, language skills, veteran status, commuting habits, housing status, and income of persons residing in the United States.[1] Scheduled for April 1, 2020, the Census will collect demographic information on the more than 327 million[2] individuals residing in the United States. The information collected will provide elected officials with more accurate descriptions of the constituents they serve, determine the number of seats each state has in the United States House of Representatives, and better allocate federal funds for local community needs.

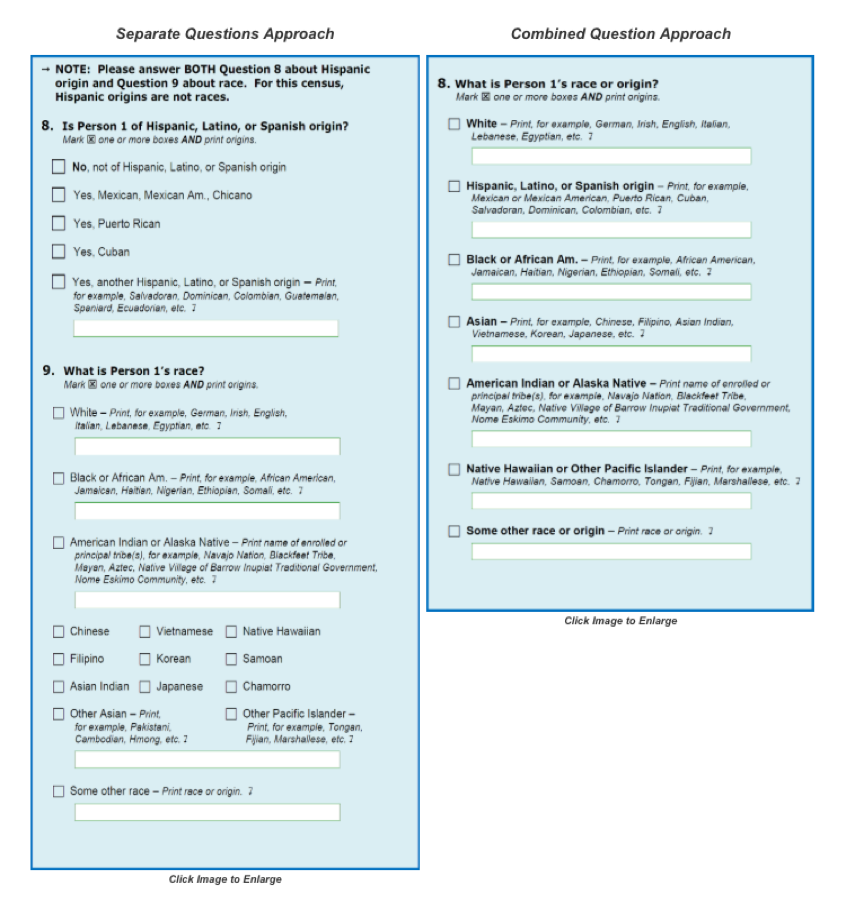

Since the 1970s, the Census Bureau has conducted content analysis tests to improve the design, validity, and functionality of the Census. Content analysis tests seek to determine whether changes to wording, response categories, and definitions of underlying constructs improve the quality of data collected.[3] Content analysis tests include several categories, such as occupation, health insurance, retirement income, race and ethnicity, commute to work, and relationships.[4] For example, the legal recognition of same-sex marriage required changes to the wording and response categories for questions on relationship status, and thus the 2016 American Community Survey (ACS) Content Test on Relationships collected data on possible revisions to questions on relationship status to include same-sex and opposite-sex spouse and same-sex and opposite-sex partner categories. The Census Bureau conducted the 2015 National Content Test Analysis Report on Race and Ethnicity (“NCT”)[5] to determine how to better reflect the shifting demographics of the United States. Namely, it sought to determine which question format would elicit better quality data on race and ethnicity, as a growing number of individuals find the racial and ethnic categories confusing or no longer identify with one of the racial categories.[6] The NCT found that the “some other race” category was the third-largest racial category in the report. In part, this was due to a majority of the Hispanic population not identifying with one of the suggested racial categories established by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). When the racial and ethnic questions were separated, the Hispanic population was more likely to select “Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish” for ethnicity and “white” or “some other race” for race. However, when the racial and ethnic questions were combined, the Hispanic population was more likely to select only “Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish”.

[7]

Here, the combined question yielded higher response rates from respondents who identify as Hispanic or Latino, providing more accurate data. The content analysis test confirms prior research that suggests Hispanic respondents are more likely to report as being only Hispanic when answering a combined question, reducing the number of “white” or “some other race” responses.[8]

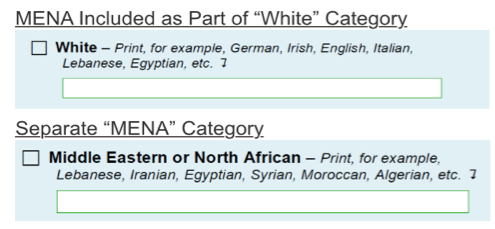

Moreover, the NCT found that when Middle Eastern or North African (“MENA”) was not included as a racial or ethnic category, those who identify as MENA were more likely to select “white” or “some other race”. When MENA was included as a separate racial or ethnic category, reporting of MENA identities significantly increased.

[9]

The findings from the NCT report suggest that the Hispanic population – the nation’s largest minority group[10] – does not identify with current racial classifications. The proposed changes could provide a better reflection of the ethnic and racial makeup of the country and decrease nonresponse rates for questions on race or ethnicity. The changes would also largely affect legislative redistricting and distribution of federal funds for education and hospitals.

However, the White House Office of Management and Budget (“OMB”) will not undertake the new changes,[11] despite years of research and support from officials in the Census Bureau. Instead, the Department of Justice is requesting the Census Bureau to include a question on citizenship on the 2020 Census for voting purposes.[12] The last time a citizenship question appeared on a Census was in 1950. Some experts fear that reintroducing a citizenship question may discourage people from participating or responding accurately. Though federal law prohibits the Census Bureau from releasing identification data on individual persons, a citizenship question may prompt a chilling effect, decreasing the accuracy of responses and undermining the goals of the Census.

Changes to the 2020 Census are still undergoing examination and analysis. The final list of questions to appear on the 2020 Census are due to Congress by March 31, 2018.

[1] https://www.census.gov/acs/www/about/why-we-ask-each-question/

[2] U.S. Population Clock: https://www.census.gov/popclock/

[3] https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2017/acs/2017_Martinez_02.pdf

[4] https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/methodology/content-test.html

[6] https://www.census.gov/about/our-research/race-ethnicity.html

[7] https://www.census.gov/people/news/issues/vol3issue6.html#3

[8] https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2017/acs/2017_Harth_01.pdf

[9] https://www.census.gov/people/news/issues/vol3issue6.html#3

[10] https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2016/cb16-ff16.html

[11] https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2018/2020-race-questions.html

[12] https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/4340651-Text-of-Dec-2017-DOJ-letter-to-Census.html

*Vanessa Miller was raised in Miami, Florida. She received her undergraduate degree in philosophy from the University of Florida and her master’s degree in philosophy and education from Teachers College, Columbia University. Her master’s thesis argued against political attempts to define education through performance-based funding.

During her master’s program, Miller was also graduate intern for the Civil Rights Bureau of the New York Attorney General’s Office. There, her research projects included educational access, ban-the-box initiatives, and housing discrimination cases. In the spring of 2014, Miller was a research assistant for a study conducted by the Columbia University Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race on the representation of Latinos in media and film.

Currently, Miller is a third-year J.D./Ph.D. candidate in higher education at The Pennsylvania State University. Her research interests include critical race theory, feminist legal theory, the use of social science research in law and policy, and the university-student relationship. She taught introductory philosophy courses at Penn State from 2016 to 2017 and has presented several papers at national conferences discussing the First Amendment on campus and the relationship between colleges and the courts. Miller is the President of the Penn State Law Latinx Law Students Association, a contributing writer for the School Law Reporter of the Education Law Association, on the board of the Public Interest Law Fund, and the Diversity Co-Chair for the Penn State Law Student Bar Association Diversity Committee. She is an extern for the Penn State Office of General Counsel, and a former extern for the Honorable Magistrate Judge Arbuckle, III in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. Last summer, she was a research assistant for the Penn State Law Civil Rights Appellate Clinic. This summer, Miller is splitting her summer with the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and the NAACP LDF in Washington, D.C.